Auditory Processing Disorder

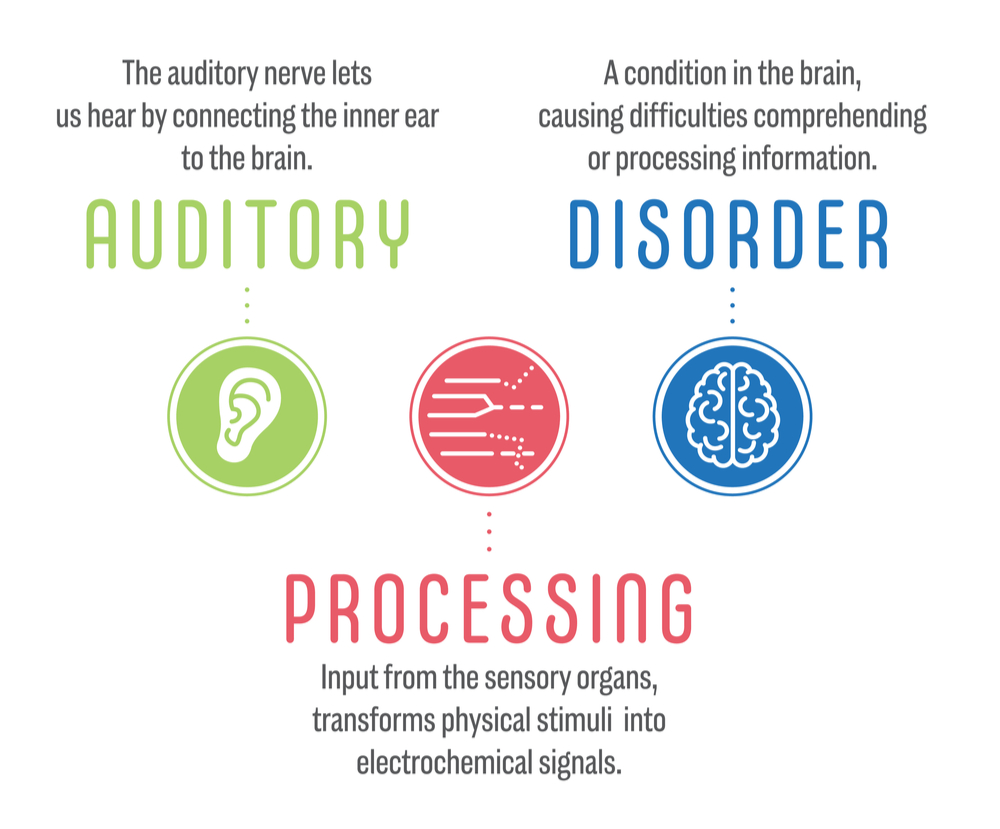

According to Geffner and Kessler’s overview, Auditory Processing Disorder (APD) refers to “what the brain does with what the ears hear.”

One example is, there was an old grandma drinking a cup of coffee and sitting with her young grandson. When the grandmother got to the bottom of her cup, she found a little green toy soldier at the bottom of the coffee cup. She looked at her grandson and he smiled and said “See, Grandma, it’s just like the TV, the best part of waking up is soldiers in your cup.”

Hearing is a very complex process. What our ears and brains do in order to hear and process information in a short amount of time is astounding. We use our hearing to communicate, learn, and interact with different environments that we encounter.

Research shows that hearing, particularly in children, is critical to language development and learning. Teaching that requires auditory feedback consists of 75-80% of all teaching in the classroom. This means that traditional academic instruction assumes that all children can hear, focus on, and understand the teacher’s voice.

Over the years, auditory processing disorder (APD) has been emerging as the “popular” disorder. Unfortunately, there a lack of clarity about the diagnosis and treatment of APD. One of the first misunderstandings is regarding the acronym used for the disorder, whether Central Auditory Processing Disorder (CAPD) or APD. Both acronyms describe the same disorder and people use them interchangeably.

What is APD?

Katz, Stecker, and Henderson (1992) described auditory processing disorder as “what we do with what we hear.” It is the ability of the brain to process incoming auditory signals. When information enters the brain, it analyzes the sound’s frequency, intensity, and temporal features. When a child receives a diagnosis of having an APD, that means there is a deficiency in the brain’s ability to interpret those characteristics.

We use six identified auditory skills to process auditory information that the ASHA (American Speech and Hearing Association) task force identified (1996):

- Sound localization/lateralization: the ability to tell where a sound is coming from.

- Auditory discrimination: the ability to hear the difference between similar sounds.

- Auditory pattern recognition: the ability to hear high versus low tones and patterns.

- Performance decrements with competing acoustic signals: trouble listening in background noise (e.g. hearing your conversation in a restaurant).

- Auditory performance decrements with degraded acoustic signals: trouble listening in less than ideal situations (e.g. classrooms).

- Temporal aspects of audition: timing of auditory information.

An auditory processing disorder is not hearing loss and cannot be identified with a typical hearing test (“raise your hand when you hear the beep”). The incidence of this disorder is 3-5% of the school-age population. There exists a gender ratio of two males affected for every female.

Skills Affected

Auditory processing skills affect a child’s ability to hear and understand words clearly. This can also affect the child’s expressive and receptive language skills, memory, attention, and cognition.

Affected auditory processing skills will result in a child hearing the word “catch” for “cat.” This will most certainly affect their ability to learn the meaning of a word. A child must be between 6-7 years of age to receive a successful diagnosis of auditory processing disorder. However, audiologists can utilize certain screening tools as early as the age of four that can suggest if a child is “at-risk” for developing APD.

Signs and Symptoms of APD

Children with APD present with behavior patterns that are initially evident in their listening skills. These problems may also suggest other issues such as learning disabilities, language problems, attention deficit, and other developmental delays. A child with auditory processing disorder may exhibit the following difficulties:

- Reading and spelling difficulties,

- Remembering more than one instruction at a time,

- Sensitivity to loud sounds,

- Slow or delayed response as compared to no response,

- Maintaining focus when they are in a setting with background noise,

- Understanding humor or sarcasm that is “heard” through inflections in voice quality,

- Understanding people with accents or rapid speakers,.

- Recognizing the direction a sound is coming from.

How Do We Evaluate for Auditory Processing Disorder?

An audiologist (hearing specialist) is the only medical professional that can diagnose an auditory processing disorder. Unfortunately, not all audiologists are equipped or trained to evaluate for APD, so it’s important that you verify this information when you call to make an appointment. The audiologist can diagnose the disorder using several testing materials that check a child’s cognition, attention, memory, family, education, etc.

Why Get an Evaluation?

- To determine if a disorder is present and, if so, what is the severity of the disorder. This will help the child in their academic and home environments. If an adolescent is being evaluated, this information is crucial to help the child understand why they are having difficulty and why certain modifications are in place.

- To rule out the disorder as a contributing factor to the child’s challenges. If the evaluation does not lead to a diagnosis of APD, it’s important for the family to receive recommendations with regard to searching for the appropriate diagnosis.

Treatment for Auditory Processing Disorder

Every child is different, which means every child’s treatment plan for APD will also be different. One medical professional that should be included in the treatment plan is a speech-language pathologist. This can be done in the school system or through a private provider.

In many states, APD is not recognized as a condition for formal resource assistance in the classroom, which means it does not qualify a child for a 504 or IEP. However, a child can fall under the umbrella of “communication impaired,” thus resulting in time with the speech pathologist at school. Sessions are typically 30-40 minutes and may not be enough for some students. Some children may require more intensive, individualized, private therapy.

By Stacie Bennett

By Stacie Bennett